Become an excellent lab book keeper

Keeping a workbook of all experiments is a daily routine for many scientists in a wide variety of disciplines. Workbooks are readily available when the hands-on work is done and it is easy to scribble anything on those pages. However, most young scientists – and sometimes older and more seasoned as well – have serious issues with writing down their experiments.

I have made so many mistakes in recording my experiments in my youth that it is just ridiculous. I have often gone back the next year or even next month and tried to understand what I wrote, why I wrote it and what was the result. Sometimes I even found it hard to understand my own handwriting.

We often write lab books (or other research notes) haphazardly because we are in a hurry. We feel that the experiment is the more important part and we will surely remember the conditions. We do not necessarily record the results, since they are presented to the lab/supervisor/boss.

This all leads to a horrible mess, and if you have ever taken over someone else’s work, reading their lab books is the first moment of exasperation in your new job. Or you might fall into your own trap when you are finally trying to publish the work you did a year ago and realize that you are not sure how you got the results you want to publish.

This is not only frustrating, but also a downright waste of money. You might do an experiment where you take blood from patients and analyse the cell types in each sample. This sort of experiment might cost thousands of dollars in reagents and your time. If you have treated your patients with something, possible for a long time, the samples can be worth tens of thousands and might not even be calculated by only financial losses, if they are from someone with a rare disease.

I will go through a list you can use when planning, executing and recording the results of your experiments. If you follow this list, you should be able to leave a trail of coherent experiments that anyone can understand.

Remember, even if ‘time loss’ feels frustrating, the time spent is not wasted, often writing it clearly helps you to outline what you are doing and how it fits into the big picture. We often miss that aspect when we are busy and concentrating on each little task at the time.

- Write your hypothesis (aims) and why you are doing this experiment. This is crucial for someone reading your lab book, but it also helps you to focus and make sure you understand it (and it is not just something your boss made you do). Question ‘why’ is an essential element in research. Hypothesis: Blueberries and strawberries make the same amount of mess on fabric. Laundry service of the restaurant is interested in this.

- Write the protocol or refer to existing SOP or protocol and attach that at the end of the lab book. SOPs and protocols might change and it is important to include the version used at that time the experiment was performed. Crush both berries on a piece of cloth, rinse it and take photos. Then wash and take photos.

-

- Write down the details: manufacturer, batch number and the equipment name/number that you are using. Berries were HealthCare brand, fabric was 100% white cotton and washed with EcoWash product by hand.

- Record the result. If it is large complex file, record where the file is stored. Photos taken before, after rinse and after wash are attached.

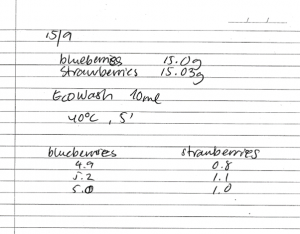

- Write a short ‘report’. Attach graph of the results or other visual aid/list that makes the result understandable or analyse the data. Write what was the result, and what is your interpretation. Write if it answers to hypothesis. 15g both berries were crushed on 10x10cm fabric cloth with kitchen knife and left for 10 min. Then rinsed with running water for 1 min. Both fabrics were put in 1L 40C water bath with 10ml EcoWash detergent and were scrunched by hands for 5 min and then rinsed with tap water. After drying, the area of any stains were measured. This was repeated three times and the average area of stains was compared. The area stained with blueberries was 5.0±0.1cm2 and strawberries 1.0±0.2cm2 and the difference was statistically significant p<0.0001 (students t-test). Hypothesis was rejected.

- Estimate your next step/experiment in the project. This will help you to bind each experiment into the big picture. Since blueberry stains are more persistent than strawberry stains, laundry service recommends its customer restaurants to prefer strawberry desserts over blueberry ones.

- Get someone to sign your lab book. Ask if they understand it. If not, write explanatory notes at the end.

- If you have made any notes on separate paper or have additional data, remember to add that data or attach the note to the lab book.

The example experiment was written in 153 words in the lab book. Plus the photos and statistical analyses. It does not require a lot of effort, but it definitely explains the experiment clearly. This is crucial in academia where employment periods are short and vast amounts of work is done by students. Most lab books I have seen are nothing like that. They generally look like the one in the picture in the beginning of this post. And remember, this takes time. You might feel tired and don’t want to do it. Do it anyway, it will pay off and will become a great habit.